Triptych – The Creation of a Gambler

By Dr. Rainer Grimm

Kaikaoss studied at the Academy in Minsk during the 1980s. His training has endowed him with a brilliant technique that recalls the precision and discipline of the old masters.

By deliberately avoiding expressive brushwork or subjective gestures, he allows the depicted objects to dominate his compositions. Each element seems to possess an autonomous presence — he creates new, self-contained worlds within his paintings that feel entirely convincing due to the perfection of their execution.

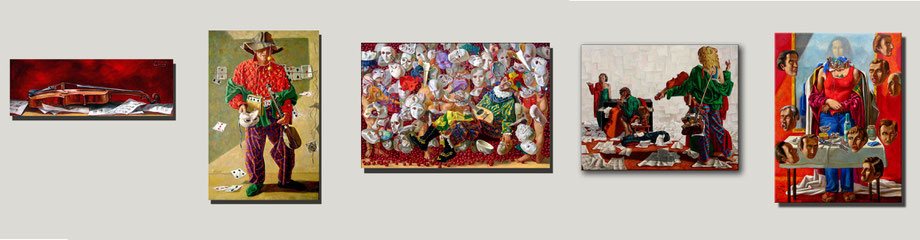

In the triptych The Creation of a Gambler, Kaikaoss explores the very idea of creation. Like a divine figure, the artist is able to invent beings and objects, arranging them in deliberate relationships.

The entire triptych measures 300 x 150 cm. Each of the three panels presents a distinct scene. A visual thread running across all three is a cord with red cloths attached. It begins in the left panel at a mast topped with porcelain insulators—reminiscent of those once used in overhead power lines—and ends in the right panel at a knob on a bedframe.

In traditional Christian triptychs, the central panel typically holds the greatest significance, so it makes sense to begin there.

We gaze into an enclosed space, its background formed by a canvas on an easel, a kind of curtain or painting featuring horses, and a green wall. In the foreground stands a table bearing human organs — a brain, male and female genitalia, a larynx — and scattered playing cards.

On the right side of the image, a figure is seated. Only the upper face, portions of the arms, and the hands are visible. The sleeves are painted in an intense ultramarine blue, standing in stark contrast to the rest of the image and commanding attention.

Though the figure is only partially visible, its position and color make it a focal point. From this figure — the creator — everything else seems to originate. Yet as the fluttering playing cards suggest, the creator here is also a gambler.

He is in the process of forming a human being. The unfinished figure stands before him, its open torso revealing ribs and organs — heart, liver, stomach, kidneys. Wings emerge from the top and sides of the figure, suggesting a hybrid between human and angel.

In the left panel, we are seemingly looking into a heavenly realm. Clouds rise upward, transforming in the lower section into a draped cloth with deep folds. Above, a blue sky appears behind the clouds, partially obscured by a hatch or panel.

A grey-bearded, youthful-bodied man sits on a green-upholstered bench. His head is propped on his hand, eyes closed — a deeply contemplative figure. Under his arm is a painter’s palette, clearly identifying him as an artist. One may reasonably interpret him as a creator as well, though one who has handed over the task of shaping the world to others. He now simply reflects.

In the right panel, we find ourselves in what appears to be an ordinary bedroom. The room ends in a green wall. A bed stands against it, with a man lying in it, only partially visible. Sitting on the edge of the bed is a naked woman, partially covered by a cloth in a vivid yellow. Her body faces forward, but her head is turned to the side. Her eyes are barely visible — she seems absorbed in inward contemplation.

The bedspread is painted in a soft blue-violet and is strongly creased. A red carpet patterned with slightly distorted squares lies on the floor. Most striking are the galloping horses scattered across the image, racing leftward, out of the frame.

Together, the three connected panels depict a vision of creation. On the left: the original creator, now passive, lost in thought. In the center: Homo Faber or Homo Ludens — the active human who now creates, primarily through play. On the right: perhaps fantasy itself, embodied by the woman, representing the realm of dreams and imagination.

Kaikaoss offers us an astonishing world through this triptych — one so meticulously painted that it feels absolutely real. Every detail is rendered with precision. Nothing is arbitrary, yet the combination of these elements evokes wonder. This is the artist’s true power — the power of the creator. He brings beings and objects into existence from nothing, makes them visible, and lets them vanish again.

All of it gestures toward another reality — a meta-reality, or a kind of hyper-reality.